Some Swell Sendak

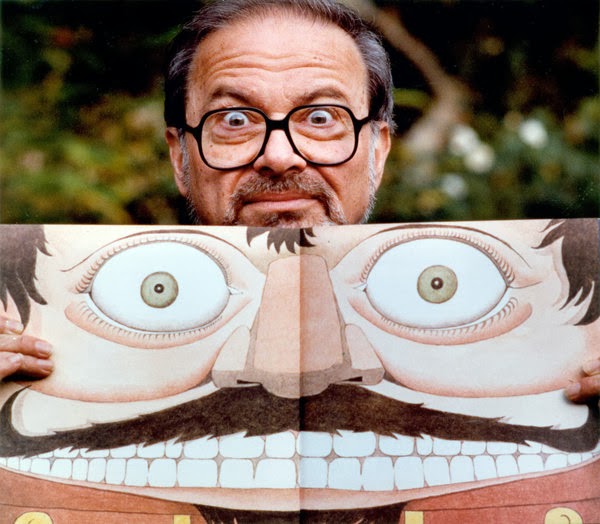

Maurice Sendak

1928-2012

1928-2012

I have focused on the art of Maurice

Sendak several times before on this blog but now I wanted to bring you a more

comprehensive look at his life and work, and include reproductions of his

artwork to show the rich variety and brilliant artistry of his illustrations

and designs. Bibliography included.

Maurice Sendak in Life, on Death,

and about His Art

|

| a drawing for "A Hole Is to Dig" |

Maurice Sendak, widely considered the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century, who wrenched the picture book out of the safe, sanitized world of the nursery and plunged it into the dark, terrifying and hauntingly beautiful recesses of the human psyche, died on Tuesday, May 8, 2012 in Danbury, Connecticut. He was 83.

Roundly praised, intermittently censored and occasionally eaten, Mr. Sendak’s books were essential ingredients of childhood for the generation born after 1960, and in turn for their children [and now for their children’s children]. He was known in particular for more than a dozen picture books he wrote and illustrated himself, most famously “Where the Wild Things Are,” which was simultaneously genre-breaking and career-making when it was published by Harper & Row in 1963.

Some

reviewers did think the book might be too frightening for children. In a Jan.

22, 1966, New Yorker profile of

Sendak, Nat Hentoff collects several of the critical responses. "We should

not like to have it left about where a sensitive child might find it to pore

over in the twilight," stated the Journal of Nursery Education.

Publishers' Weekly offered a mix of praise and criticism, saying that "the plan and technique of the illustrations are superb. … But they may well prove frightening, accompanied as they are by a pointless and

confusing story."

Library Journal's critic wrote, "This is the kind of story that many adults will question and for many reasons, but the child will accept it wisely and without inhibition, as he knows it is written for him."

Publishers' Weekly offered a mix of praise and criticism, saying that "the plan and technique of the illustrations are superb. … But they may well prove frightening, accompanied as they are by a pointless and

Library Journal's critic wrote, "This is the kind of story that many adults will question and for many reasons, but the child will accept it wisely and without inhibition, as he knows it is written for him."

Perhaps

the most insightful review harvested by Hentoff came from the Cleveland

Press: "Boys and girls may have to shield their parents from this

book. Parents are very easily scared."

Sendak didn't limit his career to a safe and successful formula of conventional children's books, though it was the pictures he did for wholesome works such as Ruth Krauss' "A Hole Is To Dig" and Else Holmelund Minarik's "Little Bear" that launched his career.

|

| Little Bear |

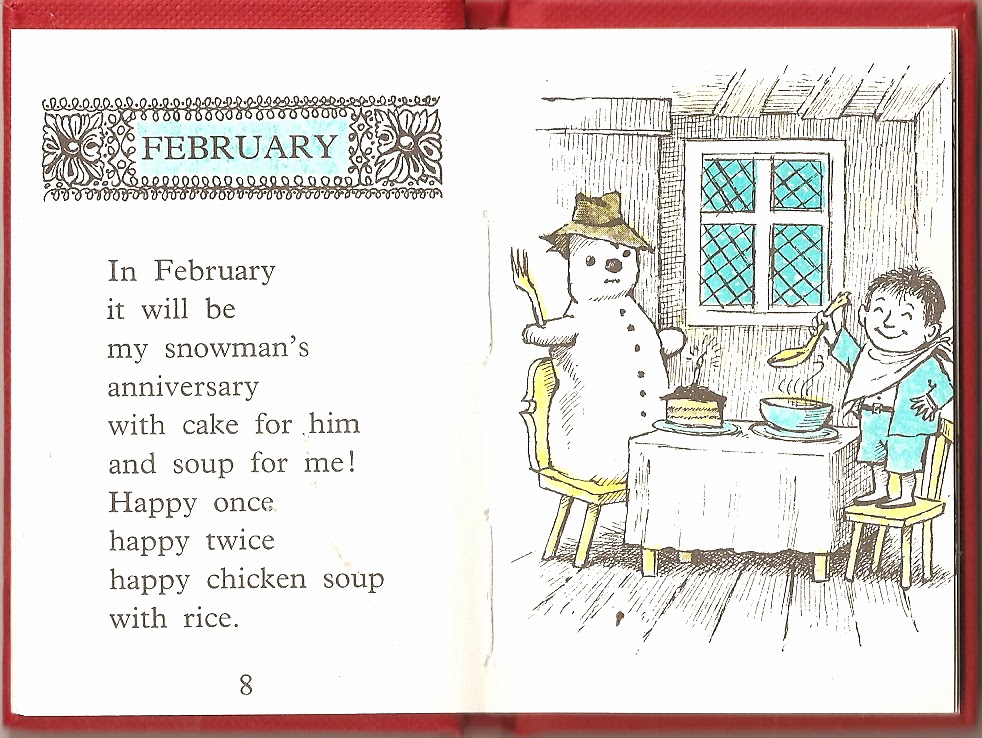

Among the other titles he wrote and illustrated, all from Harper & Row, are “In the Night Kitchen” (1970) and “Outside Over There” (1981), which together with “Where the Wild Things Are” form a trilogy; “The Sign on Rosie’s Door” (1960); “Higglety Pigglety Pop!” (1967); and “The Nutshell Library” (1962), a boxed set of four tiny volumes comprising “Alligators All Around,” “Chicken Soup with Rice,” “One Was Johnny” and “Pierre.”

|

| from "Outside Over There" |

|

| from "The Sign on Rosie's Door" |

|

| from "Nutshell Library: Chicken Soup with Rice" |

In September [2011], a new picture book by Mr. Sendak,

“Bumble-Ardy” — the first in 30 years for which he produced both text and

illustrations — was issued by HarperCollins Publishers. The book, which spent

five weeks on the New York Times children’s best-seller list, tells the

not-altogether-lighthearted story of an orphaned pig (his parents are eaten)

who gives himself a riotous birthday party.

Mr. Sendak [said] that he worked on Bumble-Ardy while taking care of his longtime

partner, Eugene Glynn, who died of lung cancer in 2007.

"When I did Bumble-Ardy, I was so intensely aware of

death," he says. "Eugene, my friend and partner, was dying here in

the house when I did Bumble-Ardy.

"I did Bumble-Ardy to save myself. I did not want to die with him. I wanted to live as any human being does. But there's no question that the book was affected by what was going on here in the house…

"I did Bumble-Ardy to save myself. I did not want to die with him. I wanted to live as any human being does. But there's no question that the book was affected by what was going on here in the house…

Bumble-Ardy was

a combination of the deepest pain and the wondrous feeling of coming into my

own.”

A posthumous picture book, “My Brother’s Book” —

a poem written and illustrated by Mr. Sendak and inspired by his love for his

late brother, Jack — is scheduled to be published next February. [It is now

available]

A posthumous picture book, “My Brother’s Book” —

a poem written and illustrated by Mr. Sendak and inspired by his love for his

late brother, Jack — is scheduled to be published next February. [It is now

available]

His art graced the writing of other

eminent authors for children and adults, including Hans Christian Andersen, Leo

Tolstoy, Herman Melville, William Blake and Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Mr. Sendak’s characters are

headstrong, bossy, even obnoxious. (In “Pierre,” “I don’t care!” is the

response of the small eponymous hero to absolutely everything.)

His pictures are often unsettling. His plots are fraught with rupture: children are kidnapped, parents disappear, a dog lights out from her comfortable home.

His pictures are often unsettling. His plots are fraught with rupture: children are kidnapped, parents disappear, a dog lights out from her comfortable home.

|

| from "Hector Protector" |

His visual style could range from intricately

crosshatched scenes that recalled 19th-century prints to airy watercolors

reminiscent of Chagall to bold, bulbous figures inspired by the comic books he

loved all his life, with outsized feet that the page could scarcely contain. He

never did learn to draw feet, he often said.

In 1964, the American Library Association

awarded Mr. Sendak the Caldecott Medal considered the Pulitzer Prize of children’s

book illustration, for “Where the Wild Things Are.”

In simple, incantatory language, the book told the story of Max, a naughty boy who rages at his mother and is sent to his room without supper. A pocket Odysseus, Max promptly sets sail:

In simple, incantatory language, the book told the story of Max, a naughty boy who rages at his mother and is sent to his room without supper. A pocket Odysseus, Max promptly sets sail:

And he sailed off through night and day

and in and out of weeks

and almost over a year

to where the wild things are.

There, Max leads the creatures in a frenzied rumpus before sailing home, anger spent, to find his supper waiting.

As portrayed by Mr. Sendak, the wild things are

deliciously grotesque: huge, snaggletoothed, exquisitely [hairy] and glowering

maniacally. He always maintained he was drawing his relatives — who, in his

memory at least, had hovered like a pack of middle-aged gargoyles above the

childhood sickbed to which he was often confined. These aunts and uncles always said that they wanted

to “eat him up.”

Maurice Bernard Sendak was born in Brooklyn on June 10, 1928; his father, Philip, worked in the garment district of Manhattan. Family photographs show the infant Maurice, or Murray as he was then known, as a plump, round-faced, slanting-eyed, droopy-lidded, arching-browed creature — looking, in other words, exactly like a baby in a Maurice Sendak illustration. Mr. Sendak adored drawing babies, in all their fleshy petulance.

|

| Sendak used the photo of himself as a baby for this drawing in "Fly by Night" |

|

| Does this baby look familiar? From "Higglety Pigglety Pop!" |

|

| This baby is not a self-portrait, but definitely fits the description "fleshy," from "Juniper Tree: The Goblins," frontispiece |

In the book "In Grandpa's House," Maurice Sendak's father Philip Sendak relates the story of his early life, and his immigration to America. He has this to say about the family circumstances at the time of the birth of his third child Maurice:

"...I left to start our own factory, which we called Lucky Stitching.

"Jackie was born. He looked like an old man, thin and homely. Then he grew more beautiful.

"Four years later Wall Street crashed, and because business was bad, our factory had to close down. I went to look for a job again.

"Maurice was born. Dr. Brummer said the child would not have a natural birth. The doctor put his instruments in a big pot and boiled them. With the tongs he took the little head and turned it, and Maurice came out all by himself...Maurice's laugh was a little bell."

|

| from "In Grandpa's House" |

Mr. Sendak was reared in a world of looming

terrors: the Depression; World War II; the Holocaust; the seemingly infinite

vulnerability of children to danger. The annihilation of the family during the

Holocaust created a profound sense of guilt even in the young Maurice, who

wrestled with the topic throughout his life. His 2003 Brundibar is a magisterial distillation of this

theme. The Yiddish language and Jewish customs that filled his household infused

most of his books with Old World stories, images, and an ever-present sense of

loss.

Mr. Sendak was sickly as a

child and could rarely join other children in their play, but his gift for

storytelling brought the whole neighborhood to the front steps of the Sendak

home, where he would regale them with stories. He was captivated by news

stories and cultural developments of the 1920s and 1930s alike, from the

introduction of Mickey Mouse in 1928 (the source of a lifelong collecting

interest in his “1928 twin”), to the New York World’s Fair in 1939 (where his older

sister ditched him, an experience he transformed into In the Night Kitchen in 1971).

An image from the Lindbergh crime scene — a ladder leaning against the side of a house — would find its way into “Outside Over There,” in which a baby is carried off by goblins.

|

| from"Outside Over There" |

|

| "We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy" |

But Mr. Sendak could also be warm and

forthright, if not quite gregarious. He was a man of many enthusiasms — for

music, art, literature, argument and the essential rightness of children’s

perceptions of the world around them. He was also a mentor to a generation of

younger writers and illustrators for children, several of whom, including

Arthur Yorinks, Richard Egielski and Paul O. Zelinsky, went on to prominent

careers of their own.

|

| from "Atomics for the Millions" |

As far back as he could remember, Mr. Sendak had loved to draw. That and looking out the window had helped him pass the long hours in bed. While he was still in high school — at Lafayette in Brooklyn — he worked part time for All-American Comics, filling in backgrounds for book versions of the “Mutt and Jeff” comic strip. His first professional illustrations were for a physics textbook, “Atomics for the Millions,” published in 1947.

|

| from "The Wonderful Farm" |

In 1948, at 20, he took a job building window displays for F. A. O. Schwarz. Through the store’s children’s book buyer, he was introduced to Ursula Nordstrom, the distinguished editor of children’s books at Harper & Row. The meeting, the start of a long, fruitful collaboration, led to Mr. Sendak’s first children’s book commission: illustrating “The Wonderful Farm.” by Marcel Aymé, published in 1951.

Under Ms. Nordstrom’s guidance, Mr. Sendak went

on to illustrate books by other well-known children’s authors, including

several by Ruth Krauss, notably “A Hole Is to Dig” (1952), and Else Holmelund

Minarik’s “Little Bear” series.

The first title he wrote and illustrated himself, “Kenny's Window," published in 1956, was a moody, dreamlike story about a lonely boy’s inner life.

|

| from "Kenny's Window" |

The first title he wrote and illustrated himself, “Kenny's Window," published in 1956, was a moody, dreamlike story about a lonely boy’s inner life.

Mr. Sendak’s books were often a window on his own experience. “Higglety Pigglety Pop! Or, There Must Be More to Life” was a valentine to Jennie, his beloved Sealyham terrier, who died shortly before the book was published.

At the start of the story, Jennie, who has

everything a dog could want — including “a round pillow upstairs and a square

pillow downstairs” — packs her bags and sets off on her own, pining for

adventure. She finds it on the stage of the World Mother Goose Theatre, where

she becomes a leading lady. Every day, and twice on Saturdays, Jennie, who

looks rather like a mop herself, eats a mop made out of salami. This makes her

very happy.

“Hello,” Jennie writes in a satisfyingly articulate letter to her master. “As you probably noticed, I went away forever. I am very experienced now and very famous. I am even a star. ... I get plenty to drink too, so don’t worry.”

“Hello,” Jennie writes in a satisfyingly articulate letter to her master. “As you probably noticed, I went away forever. I am very experienced now and very famous. I am even a star. ... I get plenty to drink too, so don’t worry.”

|

| A young Sendak with Jennie |

|

| from "In the Night Kitchen" |

The opera, also called “Brundibar,” had been composed in

1938 by Hans Krasa, a Czech Jew who later died in Auschwitz.

Reviewing the book in The New York Times Book Review, the novelist and children’s

book author Gregory Maguire called it “a capering picture book crammed with

melodramatic menace and comedy both low and grand.”

But it was "Brundibar," a folk tale

about two children who need to earn enough money to buy milk for their sick

mother that Sendak completed when he was 75, of which he was most proud.

"This is the closest thing to a perfect child I've ever had."

With Mr. Kushner, Mr. Sendak collaborated on a

stage version of the opera, performed in 2006 at the New Victory Theater in New

York.

Despite its wild popularity, Mr. Sendak’s work

was not always well received critically. Some early reviews of “Where the Wild

Things Are” expressed puzzlement and outright unease.

“In the Night Kitchen,” which depicts its young

hero, Mickey, in the nude, prompted many school librarians to bowdlerize the book by drawing a diaper over Mickey's nether region.

But these were minority responses. Mr. Sendak’s

other awards include the Hans Christian Andersen Award for Illustration, the

Laura Ingalls Wilder Award and, in 1996, the National Medal of the Arts, presented

by the President of the United States. Twenty-two of his titles have been named

New York Times best-illustrated books of the year.

"I write books as an old man, but in this

country you have to be categorized, and I guess a little boy swimming in the nude

in a bowl of milk (as in `In the Night Kitchen') can't be called an adult

book," he told The Associated Press in 2003.

"I write books as an old man, but in this

country you have to be categorized, and I guess a little boy swimming in the nude

in a bowl of milk (as in `In the Night Kitchen') can't be called an adult

book," he told The Associated Press in 2003.

"So I write books that seem more suitable

for children, and that's OK with me. They are a better audience and tougher

critics. Kids tell you what they think, not what they think they should

think."

From Maurice Sendak's Caldecott Medal Acceptance

This

talk will be an attempt to answer a question. It is one that is frequently put

to me, and it goes something like this: Where did you ever get such a crazy,

scary idea for a book? Of course the question refers to Where the Wild Things Are. My on-the-spot answer always amounts to

an evasive “Out of my head.” And that usually provokes a curious and

sympathetic stare at my unfortunate head, as though--à la Dr. Jekyll—I were

about to prove my point by sprouting horns and a neat row of pointy fangs. …

I

have watched children play many variations of this game. They are the necessary

games children must conjure up to combat…fear, anger, hate, frustration—all the

emotions that are an ordinary part of their lives… To master these forces,

children turn to fantasy: that imagined world where disturbing emotional

situations are solved to their satisfaction. Through fantasy, Max, the hero of

my book, discharges his anger against his mother, and returns to the real world

sleepy, hungry, and at peace with himself. …

I

have watched children play many variations of this game. They are the necessary

games children must conjure up to combat…fear, anger, hate, frustration—all the

emotions that are an ordinary part of their lives… To master these forces,

children turn to fantasy: that imagined world where disturbing emotional

situations are solved to their satisfaction. Through fantasy, Max, the hero of

my book, discharges his anger against his mother, and returns to the real world

sleepy, hungry, and at peace with himself. …

What is too often overlooked is the fact that from their earliest years children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions, that fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday lives, that they continually cope with frustration as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming Wild Things.

|

| Maurice Sendak in Munich, Germany, 1971 |

From Maurice Sendak's Caldecott Medal Acceptance

I

believe I can try to answer it now if it is rephrased as follows: What is your

vision of the truth, and what has it to do with children?

Last

fall, soon after finishing Where the Wild

Things Are, I sat on the front porch of my parents’ house in Brooklyn and

witnessed a scene [that could have been given the title] “Arnold the Monster.”

Arnold

was a tubby, pleasant-faced little boy who could instantly turn himself into a

howling, groaning, hunched horror. His willing victims were four giggling

little girls, whom he chased frantically around parked automobiles and up and

down front steps. The girls would flee, hiccupping and shrieking, “Oh, help!

Save me! The monster will eat me!” And Arnold would lumber after them, rolling

his eyes and bellowing. The noise was ear-splitting, the proceedings were

fascinating. …

The

game ended in a collapse of exhaustion. Arnold dragged himself away, and the

girls went off with a look of sweet peace on their faces. A mysterious inner

battle had been played out, and their minds and bodies were at rest, for the

moment.

What is too often overlooked is the fact that from their earliest years children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions, that fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday lives, that they continually cope with frustration as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming Wild Things.

It

is my involvement with this inescapable fact of childhood—the awful

vulnerability of children and their struggle to make themselves King of All

Wild Things—that gives my work whatever truth and passion it may have.

[1964]

Many of Maurice Sendak’s books had second lives on

stage and screen. Among the most notable adaptations are the operas “Where the

Wild Things Are” and “Higglety Pigglety Pop!” by the British composer Oliver

Knussen, and a collaboration with Carole King: “Really Rosie,” a musical

version of “The Sign on Rosie’s Door,” which appeared on television as an

animated special in 1975 and on the Off Broadway stage in 1980.

In 2009, a feature film version of “Where the

Wild Things Are” — part live action, part animated — by the director Spike

Jonze opened to favorable notices. Maurice Sendak said that the film reflected more of what he originally intended for the story of Max and his Wild Things.

|

| Theater poster for stage production |

|

| scene from the film "Where the Wild Things Are" |

In the 1970s, Mr. Sendak began designing sets and costumes for adaptations of his own work and, eventually, the work of others. His first venture was Mr. Knussen’s “Wild Things,” for which Mr. Sendak also wrote the libretto. Performed in a scaled-down version in Brussels in 1980, the opera had its full premiere four years later, to great acclaim, staged in London by the Glyndebourne Touring Opera.

|

| "The Cunning Little Vixen" sets and costumes by Sendak |

For the Pacific Northwest Ballet, Mr. Sendak

designed sets and costumes for a 1983 production of Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker”;

a film version was released in 1986.

|

| A playful Sendak with a Nutcracker illustration |

Among Mr. Sendak’s recent books is his only pop-up book, “Mommy?” published by Scholastic in 2006, with a scenario by Mr. Yorinks and incredible paper engineering by Matthew Reinhart.

Though he understood children deeply, Mr. Sendak

by no means valorized them unconditionally. “Dear Mr. Sun Deck ...” he could

drone with affected boredom, imitating the forced-march school

letter-writing projects of which he was the frequent, if dubious, beneficiary.

But he cherished the letters that individual

children sent him unbidden, which burst with the sparks that his work had

ignited.

“ 'Dear Mr. Sendak,' read one, from an 8-year-old boy. 'How much

does it cost to get to where the wild things are? If it is not expensive, my

sister and I would like to spend the summer there. Please answer

soon.' I did not answer that question, for I have no doubt that sooner or later

they will find their way, free of charge."

"Despite the fact that I don't write with children in mind, I long ago discovered that they make the best audience. They certainly make the best critics. ...When children love your book, it's 'I love your book, thank you. I want to marry you when I grow up.' Or it's 'Dear Mr. Sendak: I hate your book. Hope you die soon. Cordially...' "

"Despite the fact that I don't write with children in mind, I long ago discovered that they make the best audience. They certainly make the best critics. ...When children love your book, it's 'I love your book, thank you. I want to marry you when I grow up.' Or it's 'Dear Mr. Sendak: I hate your book. Hope you die soon. Cordially...' "

"Once a little boy sent me a charming card with a little drawing on it. I loved it. I answer all my children’s letters — sometimes very hastily — but this one I lingered over. I sent him a card and I drew a picture of a Wild Thing on it. I wrote, 'Dear Jim: I loved your card.' Then I got a letter back from his mother and she said, 'Jim loved your card so much he ate it.' That to me was one of the highest compliments I’ve ever received. He didn’t care that it was an original Maurice Sendak drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it."

|

| Sendak in his studio with Roger Sutton of Horn Book Magazine |

Here is another excerpt from "In Grandpa's House" by Philip Sendak: "I lived my whole life in Brooklyn, and everything was alright. My wife was never ill. Now I am alone. I have lost my wife, and everything is a blank to me. When I close my eyes, I see her and she wants to talk. I ask her what she wants, but she doesn't answer.

"My children try to make me forget. My son asks me to write a children's story. I have tried many times, but nothing comes. When I was young, I heard so many stories and was able to tell wonderful tales. Now I am seventy-five, I can no longer imagine myself in a child's life.

"But since I have nothing else to do, I will write a story that my father told us when I was a child.

"Little children, be still! I will tell you a story, my papa would say. And when it was quiet, and the children opened their mouths and ears, he began his tale."

This legacy of story, of sorrow, and of struggle was given to his son, along with a marvelous ability to paint it.

|

| Maurice Sendak on his property in Connecticut |

A final word about Maurice Sendak's last work, published posthumously, "My Brother's Book," from an article in Publishers' Weekly:

|

| from "My Brother's Book" |

Sendak was already in the hospital when he saw the final layout; he was “delighted, ecstatic” with it, di Capua [his editor] remembers. It was his last look at the book. He died four days later...

At the end of a 2006 New Yorker profile, Sendak said, “When my brother Jack died, I wanted to do something extraordinary for him. Five years later, I had an idea. The poem I wrote was very dark. I hope to finish it.”

He did finish it, and in the finishing it grew to be more than just a poem for Jack. It was a fearless and tender look at his own fate, and a farewell gift to all who loved his work.

|

| with his friend Herman |

Excerpted from obituaries, interviews, speeches, and articles from the Associated Press, published in the Huffington Post, The New York Times in May of 2012, from Rosenbach.org, and also from a New Yorker article by Nat Hentoff.

Books Written and Illustrated by Maurice Sendak

1956 Kenny's Window

1957 Very Far Away

1960 The Sign on Rosie's Door

1962 The Nutshell Library

- Alligators

All Around (An Alphabet)

- Chicken

Soup with Rice (A Book of Months)

- One Was

Johnny (A Counting Book)

- Pierre (A

Cautionary Tale)

1963 Where the Wild Things Are

1967 Higglety Pigglety Pop! Or, There Must Be More to Life

1970 In the Night Kitchen

1970 Ten Little Rabbits: A Counting Book with Mino the

Magician

1975 Maurice Sendak’s Really

Rosie Starring the Nutshell Kids (with songs by Carole King)

1975 Seven Little Monsters (this is the date of the

first publication of this work which was in Switzerland, first U.S. edition:

1977)

1976 Posters by Maurice

Sendak

1976 Some Swell Pup or Are You Sure You Want a Dog? (with co-author Matthew Margolis)

1981 Fantasy Sketches

1981 Fantasy Sketches

1981 Outside Over There

1988 Cover art for Caldecott and Co: Notes on Books and Pictures (an anthology of essays on children’s

literature)

1995 Maurice Sendak’s Christmas Mystery (a box containing a book and jigsaw

puzzle)

2011 Bumble-Ardy

2013 My Brother’s Book,

published posthumously

Illustrated by Maurice Sendak and Written by Other Authors

1947 Atomics for the Millions (Dr. Maxwell Leigh Eidinoff)

1951 The Wonderful Farm (Marcel Aymé)

1951 The Wonderful Farm (Marcel Aymé)

1951 Good Shabbos Everybody (Robert Garvey)

1952 A Hole is to Dig: A First Book of First Definitions (Ruth Krauss)

1952 Maggie Rose, Her

Birthday Christmas (Ruth Sawyer)

1953 A Very Special House (Ruth Krauss)

1953 Hurry Home Candy (Meindert DeJong)

1953 The Giant Story (Beatrice Schenk de Regniers)

1954 I’ll Be You and You Be Me (Ruth Krauss)

1954 Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s Farm (Betty MacDonald)

1954 The Tin Fiddle (Edward Tripp)

1954 The Wheel on the School (Meindert DeJong)

1955 Charlotte and the White Horse (Ruth Krauss)

1955 Charlotte and the White Horse (Ruth Krauss)

1955 Happy Hanukah Everybody (Hyman and Alice Chanover

1955 Little Cow & the Turtle (Meindert DeJong)

1955 Singing Family of the Cumberlands (Jean Ritchie)

1955 Seven Little Stories on Big Subjects (Gladys Baker Bond)

1955 What Can You Do with a Shoe? (Beatrice Schenk de Regniers)

reissued in 1997 with full-color illustrations

1956 The Happy Rain (Jack Sendak, Maurice Sendak’s brother)

1956 The House of Sixty Fathers (Meindert DeJong)

1956 I Want to Paint My Bathroom Blue (Ruth Krauss)

1957 The Birthday Party (Ruth Krauss)

1957 Circus Girl (by Jack Sendak, Maurice Sendak’s

brother)

1957-1968 Little Bear Series (Else Holmelund Minarik).

- Little

Bear (1957)

- Father

Bear Comes Home (1959)

- Little

Bear's Friend (1960)

- Little

Bear's Visit (1961)

- A Kiss for

Little Bear (1968)

1957 You Can’t Get There from Here (Ogden Nash)

1958 Along Came a Dog (Meindert DeJong)

1958 No Fighting, No Biting! (Else Holmelund Minarik)

1958 What Do You Say, Dear? (Sesyle Joslin)

1959 Seven Tales by H. C. Andersen (Eva Le Gallienne, translator)

1959 The Moon Jumpers (Janice May Udry)

1960 Open House for Butterflies (Ruth Krauss)

1960 Windy Wash Day and Other Poems (Dorothy Aldis) for the collection:

Best in Children's Books: Volume 31

1960 Dwarf Long-Nose (Wilhelm Hauff,

author; Doris Orgel, translator)

1961 What the Good-Man Does Is Always Right (Hans Christian Andersen) for the collection: Best in Children's Books: Volume 41

1961 Let's Be Enemies (Janice May Udry)

1961 What Do You Do, Dear? (Sesyle Joslin)

1961 Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present (Charlotte Zolotow)

1962 The Big Green Book (by Robert Graves)

1962 The Singing Hill (Meindert DeJong)

1962 The Singing Hill (Meindert DeJong)

1963 The Bat-Poet (Randall Jarrell)

1963 The Griffin and the Minor Canon (Frank R. Stockton)

1963 How Little Lori Visited Times Square (Amos Vogel)

1963 Sarah’s Room (Doris Orgel)

1963 She Loves Me...She Loves Me Not... (Robert Keeshan, aka Captain Kangaroo)

1964 The Bee-Man of Orn (Frank R. Stockton)

1964 The Bee-Man of Orn (Frank R. Stockton)

1965 The Animal Family (Randall Jarrell)

1965 Hector Protector and As I Went Over the Water: Two Nursery

Rhymes (traditional)

1965 Lullabies and Night Songs (Alec Wilder, composer; William Engvick, editor)

1966 Zlateh The Goat and Other Stories (Isaac Bashevis Singer)

1967 The

Golden Key (George MacDonald)

1969 The Light Princess (George MacDonald)

1971 Somebody Else’s Nut

Tree and Other Tales from Children (Ruth Krauss)

1972 Cover art and design for Down

the Rabbit Hole: Adventures and Misadventures in the Realm of Children’s

Literature (Selma G. Lanes)

1973 King Grisly-Beard: A Tale from the Brothers Grimm

(Edgar Taylor, translator)

1973 The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm

(Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, selected by Lore Segal and Maurice Sendak, translated

by Lore Segal and Randall Jarrell)

1974 Cover art for Hans

Christian Andersen: The Complete Fairy Tales & Stories, translated from

the Danish by Erik Christian Haugaard

1975 Pleasant Fieldmouse (Jan Wahl)

1976 Fly by Night (Randall Jarrell)

1977 Shadrach (Meindert DeJong)

1978 The Big Green Book (Robert Graves)

1979 Frontispiece for The

Portent (George MacDonald)

1983 Jacket drawing for Kleist,

a Biography (Joachim Maass)

1984 The Love for Three Oranges: The Glyndebourne

Version (Frank Corsaro, author with Maurice Sendak, based on L'Amour

des Trois Oranges, by Serge Prokofiev)

1984 Nutcracker (E.T.A. Hoffman)

1985 In Grandpa's House (Philip Sendak, Maurice Sendak’s

father)

1985 The Cunning Little Vixen (Rudolf Tesnohlidek)

1988 Dear Mili (Wilhelm Grimm)

1988 Story Poems for the

collection Sing a Song of Popcorn:

Every Child’s Book of Poems (selected

by Beatrice Schenk de Regniers, Eva Moore, Mary Michaels White, and Jan Carr)

1990 Cover Art and

Illustration for the collection The

Big Book for Peace (various

authors and illustrators)

1992 I Saw Esau: The Schoolchild’s Pocket Book (Iona and Peter Opie, editors)

1992 I Saw Esau: The Schoolchild’s Pocket Book (Iona and Peter Opie, editors)

1993 We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy: Two Nursery Rhymes

1995 The Miami Giant (Arthur Yorinks)

1995 The Miami Giant (Arthur Yorinks)

1995 Pierre: or, The Ambiguities: The Kraken Edition (Herman Melville)

1996 Frank & Joey Go to Work (a board book, written and directed by Arthur Yorinks; set and costumes by Maurice Sendak; photography by Ky Chung)

1996 Frank & Joey Go to Work (a board book, written and directed by Arthur Yorinks; set and costumes by Maurice Sendak; photography by Ky Chung)

1996 Frank & Joey Eat

Lunch (a board book, written and directed by Arthur Yorinks; set and

costumes by Maurice Sendak; photography by Ky Chung)

1997 What Can You Do with a Shoe? (Beatrice Schenk de Regniers) a

reissue with full-color illustrations

1998 Penthesilea (Heinrich von Kleist, author; Joel

Agee, translator)

1998 Swine Lake (James Marshall)

2000 Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom (Ursula Nordstrom, author; Leonard S.

Marcus, editor)

2000 A Perfect Friend (Reynolds Price)

2003 Brundibar (Tony Kushner)

2003 Brundibar (Tony Kushner)

2005 Bears! (Ruth Krauss) this story was originally

published with illustrations by Phyllis Rowand in 1948 by Harper & Bros.

2006 Mommy? [Sendak’s only pop-up book] (Scenario

by Arthur Yorinks, Paper Engineering by Matthew Reinhart)

Books Written About Sendak and his Work.

_cover.jpg)

.jpg)

Sehr geehrter Herr Archibald!

ReplyDeleteIhr Text über Sendak gefällt mir sehr!

DANKE!

Besonders gefällt mir der Hinweis, dass Sendak das mürrische Gesicht des kleinen Maurice später für viele von ihm gezeichnete Gesichter verwendet!

Einfach Klasse diese Erkenntnis von Ihnen!

Veit Feger

veit-feger.homepage.t-online.de